February 04, 2014

When I worked in LA as an industrial designer for Mattel, one of their art directors told me once that a model I'd spent days making was perfect except that it needed to be about 5% smaller. Those of us accustomed to that sort of work and dealing with professional clients have all had similar experiences at one time or another. Such deflating and anti-climactic 'reveals' after hours and hours of labor can be a blow leading to a domino effect of other delayed projects, marathons in the workshop (I worked 26 hours straight once), and cancelled recreational plans. But they can also present thrilling challenges that provide a bit of spice to one's life, and a real sense of accomplishment when something that seemed impossible is successfully completed.

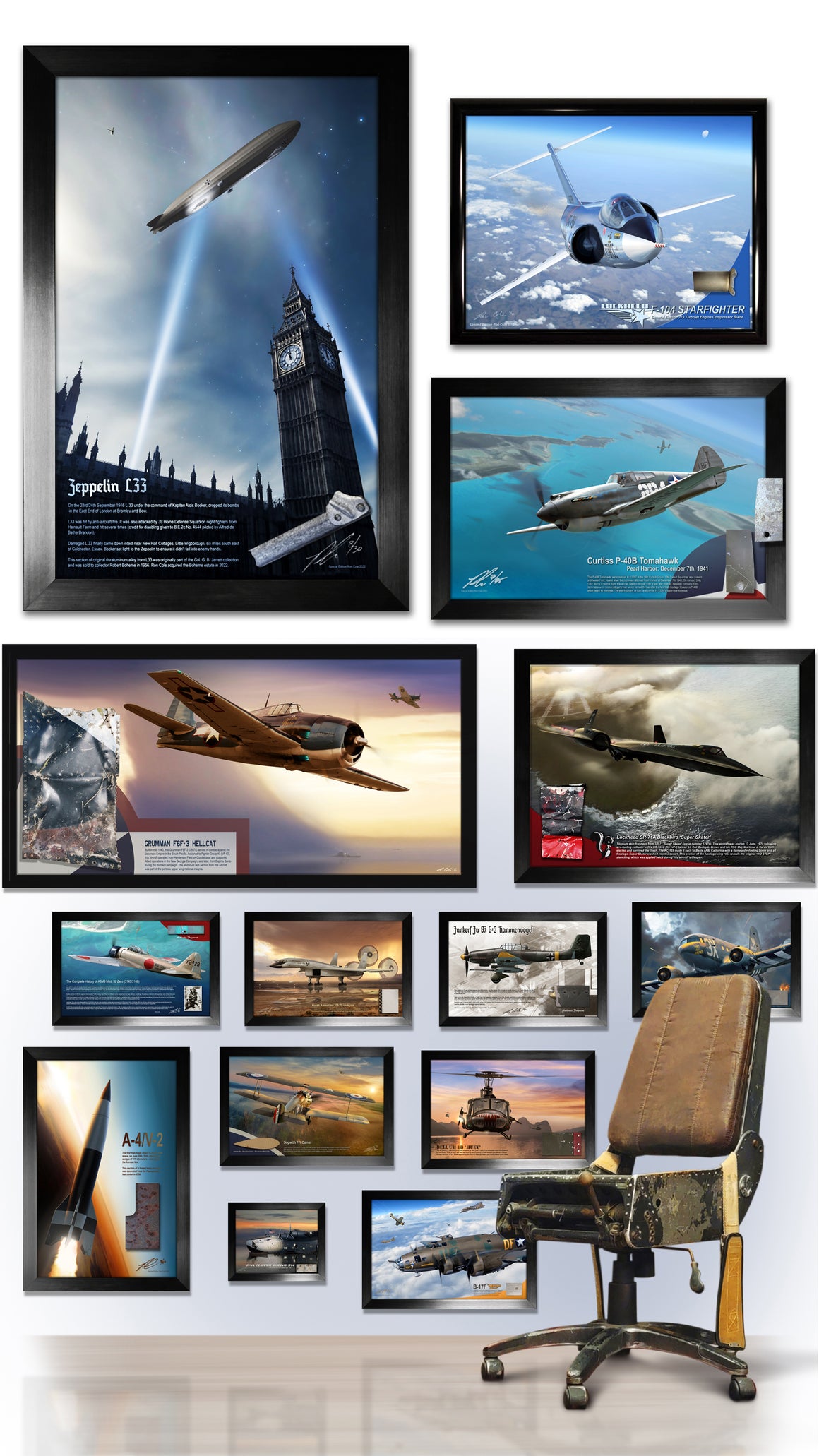

Case in point: When Historic Aviation contacted me to do their cover art for their January/February 2014 catalog, I was pretty excited. With a circulation of over 400,000, the business marketing side of me saw how that kind of exposure would be fantastic for my business. Of course with that came the added pressure of feeling like I had to do something particularly spectacular, but with almost two months of lead time I wasn't too worried about it. My previous experience as a designer - where people say that it's not enough to be the best, you have to also be the fastest - had made me a very efficient artist. All speed ahead. I completed the painting in about three weeks:

They liked it when they received it, and in fact I'd shared numerous 'in progress' images of the piece as it evolved to make sure that the composition fit the page and that my overall direction was what they were looking for. I sent them the high resolution file, felt proud, and moved onto other commissions.

At about the time I was eagerly expecting to see the magazine released, I received a call from one of their art people. The head art director liked the painting, but felt that the color palate was all wrong for a magazine cover. It wouldn't 'pop' enough on the shelf. (Ironically, I knew exactly what he was talking about. I'd constructed a prototype scale motorcycle for a company once, painted it dark metallic orange, and while they loved it in almost every way - they rejected it because of the color.) I was thinking, Okay, I'll tweak the colors; maybe brighten it a bit.

No.

They asked me if I could produce a 'daylight version' of the same painting - and they needed it in three days. In my head, I heard Stewie Griffin cry, "Say whaaaaaat???" But by the end of the phone call my somewhat sheepish assurances that I could do it had become more resolute. I was trying to work out in my head how it could be done while we spoke. I could do it - almost certainly.

Of course what remained entirely uncertain was how good the results would be. Changing the light source in a finished painting is demanding enough all by itself. This would be a whole new color palate and an entirely different background. I thought I'd been so slick when I made the aircraft in my composition sport a high gloss reflective finish, and now that finish would have to reflect a completely different environment. This was hardly going to be the 'particularly spectacular' cover I'd spent three weeks painting in the first place.

Thank God for my weird artistic process. Having been an old-school acrylic on canvas painter earlier in life and a digital painter who produced architectural work for developers later in life, I'd created a way to play to the strengths of both media. One side effect of the process is that all of my work exists as high resolution .psd files with most elements in each composition saved on separate layers.

While hardly representative of the way I normally paint a painting, I think that the process through which I accomplished this drastic and last minute revision is worth describing.

Step One: The background would be a total loss; no avoiding that. It depicted a set sun located roughly behind the aircraft carrier Bunker Hill. Any daylight composition would have to put the sun somewhere out of frame above everything, or behind the viewer. All of the layers that related to the sky and clouds were deleted. The ocean surface ultimately reflected the sky and its color palate - so all of its layers were deleted. So much for all of those hours spent; so sad.

Step Two: Say 'goodbye' to all of the remaining color. In the digital realm it's usually easy to change colors, but you can't just press a button and get what you want. In this case I spent a good hour trying to see if I could manipulate the original color palate of the aircraft and other elements bit by bit, but it was obvious that this method would be more trouble than it was worth. Somewhat reluctantly, I flattened all of the remaining layers (minus the sky and water) and turned them black and white:

Talk about a regression! At this point I was essentially dealing with a very complicated colorization project, the likes of which I've done with old Civil War and WWII period photographs - except with a lot of new painting inevitably involved.

Step Three: Paint a new sky and ocean surface. I cheated here - sort of. I seldom have any reason to be thankful for the fact that I leave many painting projects unfinished and languishing about for years. In this case it was a blessing, as I was lucky enough to find a mostly completed sky with a light source appropriate for my needs. The sun was just out of frame to the upper left, which was perfect. It would justify a somewhat back-lit aircraft, and the sun's partial obstruction by thin clouds would diffuse the light and eliminate the need to paint hard shadows over everything. Wonderful! All I had to do from scratch was paint a new ocean surface, and slip the whole canvas behind all of the foreground elements:

Welcome to our new color palate! But it was not now just a matter of re-introducing these colors to all of the things that had been previously orange. The digital realm allows me to do that, insofar I can mask off areas of pixels or choose pixels of similar value and color them - but the end results never look realistic; they look like a colorized old picture. The reason for this effect is because in the real world there are frequencies of light bouncing off of everything from all sorts of primary and secondary light sources, and in that process those frequencies of light - those combinations of colors - become separated. What our human eyes seem to interpret as a specific shade of blue, for example, is in reality a hundred slightly different hues. Digital colorization does not replicate that (the third aircraft from the top reveals what it looks like to apply simple colorization techniques):

Step Four: The only thing left to do was to paint, keeping in mind the inherent attributes of the different surfaces being rendered. Glossy blue will exchange a portion of its color value with the color value of what's being reflected off of it, while the values of non-reflective surfaces will still be changed by ambient light, though not in the same way . . . all things that I believe are best learned by simply observing the real world. But the painting at this point more resembled a complex paint-by-numbers exercise; employing semi-opaque color so as not to obliterate the original forms. Some additional changes were made. The soft shadows left behind from the previous light source were painted over. The clouds that were previously reflected in the aircraft were changed to match the new background. Details, like the pilot, that had been cast in darkness from being more directly back-lit were brightened. Lights were turned off and the bright exhaust flames were painted to look more subdued. I moved some things around.

The end result, eleven hours later, looked pretty good:

Overall I'm very happy with the result - somewhat to my surprise and very much to my relief. I was able to pull off an unprecedented last minute revision with essentially two days to spare. What I have to thank for it, primarily, besides finding a good background that saved quite a bit of time, was the use of digital media. As an old-school artist who once hated the so-called 'subversion' of all that was 'genuine' about the art of painting, I used to fear what I did not then understand. Today I cannot imagine doing what I do for a living without it, because while I still believe that there is great value in the works of chemical pigments and animal hair brushes, the industry that we work in today is far more demanding than any paint on canvas alone can adapt to.

If I'd painted this painting originally on a stretched piece of canvas - I would have, without any question, lost this magazine cover. Period.

- Ron Cole

Comments will be approved before showing up.

April 19, 2024

February 16, 2014

Join our mailing list and receive 20% off your first order!